1. Introduction

As the world comes to live with SARS-CoV-2 and humanity reminded the inescapable reality of global interconnectedness. Every country would have witnessed the health, social, and emotional effects of COVID-19 pandemic. For some, these effects of COVID-19 linger till this present day. It is important to reflect and respond to the huge toll the pandemic has taken on people’s mental health worldwide. Rate of already-common mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, insomnia, etc. increased significantly during the pandemic and exacerbated by the loss of livelihoods associated with the pandemic. The mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic may shape population health for many years to come. Failure to address the mental health issues stemming from the pandemic is likely to prolong its impact. Many neurological effects of SARS-CoV-2 may be long-lasting, with an increasing consensus referring to these simply as “Long COVID”, which has been characterized by headaches, hyposmia, hypogeusia, and fatigue with more severe conditions including sleep disorders, chronic pain, cognitive impairment, and Guillain-Barré Syndrome. COVID-19 is associated with increased risks of neurological and psychiatric sequelae in the weeks and months thereafter.1 The COVID-19 pandemic has had a huge impact on public health around the globe in terms of both physical and mental health, and the mental health implications of the pandemic may continue long after the physical health consequences have resolved. Understanding how mental health evolves as a result of this serious global outbreak will inform prevention and treatment strategies moving forward, including allocation of resources to those most in need.

The burden of mental health disorders in the global community has been discussed at length in the literature and it is clear that global mental health and knowledge of the same (mental health literacy) is singularly one of biggest health challenges facing mankind.2 If one incorporates behavioral aspects of disorders in medical disciplines, maladaptive motivated behaviors of the addictions, dietary and recreational inequities created by a combination of cultural opportunities and resources, as well as personal choices influenced by the collective community economy – it should be apparent that the dimension of mental health reaches deep into a culture and its communities.3 The burden of poor mental health and its specific disorders when these are known, affect most, if not all aspects of global health. Untreated mental disorders exact a high toll, accounting for 13% of the total global burden of disease.4

2. Mental health in the general population and sense of coherence

In addition to SARS-CoV-2 severe implications to the people’s lives, the economy toppled as businesses ceased to operate and non-essential businesses were restricted from opening; hence, many people lose their jobs. As social distancing becomes a mandate, schools were closed, and mass gatherings were prohibited. Severe restriction in movements among the people was enforced to support efforts to contain and slow down the spread of the virus. The regulated movement of people brought about a “new normal” that drastically altered the way people carry out their normal daily activities; and forcing societies to adapt to this new way of life rapidly. These new life conditions add to the people’s stress as they are forced to change their daily routines. This scenario poses risks that often disturb people’s perception and disposition, causing extreme psychological pressure and burden due to overwhelming feelings of loneliness, isolation, separation anxiety, xenophobia or fear of contracting the disease, worry of availability of health care support5 and concern over spreading the disease within close circles at home and work. The significant psychological impact of such challenging time is elevated rates of stress and/or anxiety. According to the WHO (World Health Organization), in the first year of the pandemic, there was a noted increase in the prevalence of mental disorders such as anxiety and depression, equal to approximately 25%.6 For individuals with weak coping mechanisms, the effects of the pandemic may trigger mental health issues which may lead to suicidal behaviors such as suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and actual suicide. To avoid these consequences, people must learn to cope with stress positively, which boosts resilience.7 On the other hand, if a person’s stress level is not controlled and managed well, stress may exacerbate one’s pre-existing conditions and present situation. It may significantly reduce one’s level of well-being. It is, therefore, of the essence to identify the factors that modulate a person’s stress response, especially during the pandemic.

Studies show a sense of coherence (SOC) plays a significant role in ascertaining an individual’s ability to cope with stressors and is considered a resistance factor.8,9 Sense of coherence is a mixture of optimism combined with a sense of control and has the components of: a) comprehensibility (cognitive), b) manageability (behavioral), and c) meaningfulness (motivational). Comprehensibility is the extent a person rationalizes or understands both internal and external stimuli. Manageability pertains to resourcefulness in using what we have at our disposal to help manage the stimuli. And meaningfulness is the way we feel and see that our life has a purpose and emotional meaning. Irrefutably, a person’s quality of life and health outcomes are significantly influenced by one’s sense of coherence as we become mindful of internal and external factors that might trigger stress.10 Sense of coherence and mindfulness are known as protective factors that combat psychopathology even in older age groups. The higher the SOC, the less stressed or affected a person becomes. Adequate preparedness, good social support, and proactive coping styles shall also significantly reinforce resilience.

Major public mental health challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic include the protection of those with mental disorders from COVID-19 and the associated consequences, the psychological needs of health care providers, and the deterioration in mental wellbeing and increase in mental disorders in the entire population.11 In view of the ever-increasing pressure on global health systems resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, adopting and adapting “task-shifting”, i.e., the delegation of psychotherapeutic interventions to trained non-specialists, as an element of the provision of mental health services, is overdue.

3. Task-shifting in mental health care

Ideally, multidisciplinary mental health teams, consisting of psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses and clinical psychologists, should deliver mental health services. Most patients and health workers affected by COVID-19 present with adaptive emotional and behavioural responses to high levels of stress, and, thus, psychotherapy techniques based on the stress-adaptation model may be useful.12 In severe cases of mental illness, treatment by specialists is required. However, experience with disaster relief has shown that certain aspects of therapy for mental disorders can be delegated to non-specialists. This concept is known as “task-shifting”. For example, lay persons can be trained to treat mild-to-moderate depression and anxiety. When too few psychiatrists are available, these lay workers may play a useful role in the care of those most in need, such as the suicidal. Task-shifting could also be employed to support health care providers in hospitals and isolation units, where most health professionals receive no training in mental health care. Task shifting involves the rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams. Specific tasks are moved, where appropriate, from highly qualified health workers to health workers with shorter training and fewer qualifications in order to make more efficient use of the available human resources for health. Task shifting to lower educational leveled professionals emerged from the developing global community with broad applicability.

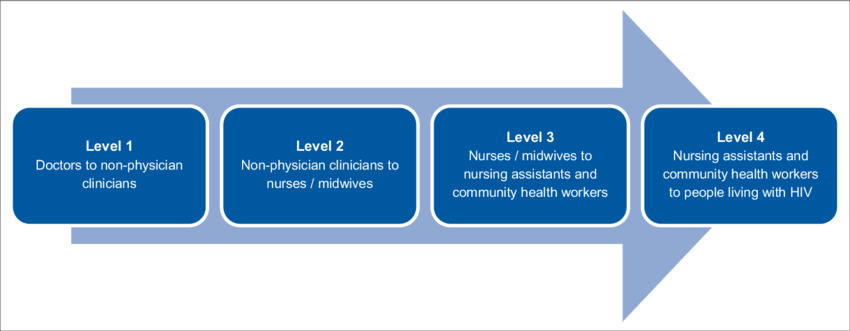

The WHO functional definition of task shifting supports a broad categorization of practices into four types, as follows:

-

Task shifting I: The extension of the scope of practice of non-physician clinicians in order to enable them to assume some tasks previously undertaken by more senior cadres (e.g. medical doctors).

-

Task shifting II: The extension of the scope of practice of nurses and midwives in order to enable them to assume some tasks previously undertaken by senior cadres (e.g. non-physician clinicians and medical doctors).

-

Task shifting III: The extension of the scope of practice of community health workers, including people living with the diseases of interest, in order to enable them to assume some tasks previously undertaken by senior cadres (e.g. nurses and midwives, non-physician clinicians and medical doctors).

-

Task shifting IV: People living with the disorders of interest, trained in self-management, assume some tasks related to their own care that would previously have been undertaken by health workers. Task shifting can also be extended to other cadres that do not traditionally have a clinical function, for example pharmacists, pharmacy technicians or technologists, laboratory technicians, administrators and records managers.

An example of successful task-shifting was the innovative health care system introduced in China in the 1960s to ensure that people living in rural communities received basic medical care.13 This system relied on large numbers of lay people, who received a modicum of medical and paramedical training, enabling them to provide prenatal care and to treat common infectious diseases. While these community health workers lacked the medical expertise of doctors, their provision of basic low-cost health care was crucial in rural areas. This approach of community generalism rather than hospital specialism has demonstrated that many diseases in poor countries can be prevented and treated without significant financial resources, provided that appropriate policies support rural-based and non-commercial forms of preventive health care and primary care therapies.14,15 Community health workers can provide needed primary care not only in lower-income countries, but also in underserved regions of higher-income countries. Given the known benefits of social support as a buffer against mental distress, interventions delivered by peers or mental health support groups should be encouraged and enhanced. Social prescribing, which is the use of non-medical interventions such as physical activity, the arts or other community engagement, is concerned with broader determinants of health and can be adopted, through the use of existing resources in communities, to improve wellbeing.16 Social prescribing has been shown to be a low-cost approach in the prevention of mental and physical health conditions.17 In mental health care, the notion that only psychiatrists and psychotherapists can provide treatment for mental illness should be abandoned. Other forms of community-based and collaborative approaches are needed. Lay health workers can and should be trained to deliver health care in non-specialist settings.

4. Conclusion and policy implication

The COVID-19 pandemic created significant global mental health challenges, especially in lower income countries. Although steps have been taken by some countries’ governments to address negative mental health impacts stemming from the pandemic, however, mental health and substance use disorders remain elevated. Since the pandemic, the frequency of mental health disorders is increasing, and represents a large portion of the global burden of human disease (DALYs). The implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for mental health call for a greater focus on the needs of those with mental disorders and on mental health issues affecting health care workers and the general population. A broader scope of global mental health beyond specific disease areas will be crucial to addressing the ongoing mental health challenges of COVID-19 and responding to future humanitarian crisis. Learning from the experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic and adapting the focus of mental health research will be vital to develop effective policy in mental health recovery efforts. Public mental health interventions that can be scaled up are needed to reduce the population impact of mental disorders across all nations and people, particularly lower income countries and socially marginalized populations

Timely preventive and therapeutic mental health care is essential in addressing the psychosocial needs of populations exposed to the pandemic. In addition to specialist care, task-shifting and digital technologies may provide cost-effective means of providing mental health care in lower-income countries worldwide as well as in higher-income countries with mental health services overwhelmed by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Digital technologies can be used to enhance social support and facilitate resilience to the detrimental mental health effects of the pandemic; they may also offer an efficient and cost-effective way to provide easy access to mental health care. It is essential to scale up adopted and adapted management strategies to sustain mental health care services worldwide as the war against the virus rages on.

Funding statement

The author received no grant or financial support from funding agency for this study.

Ethical statement

The author asserts that all procedures contributing to this study comply with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2008.

Conflict of interest

The author hereby declares no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

I am forever grateful to Jesus Christ the Great Physician for sharing in His light. I will like to express my profound gratitude to Dr. Joshua Owolabi PhD for your gentle guidance and enthusiastic encouragement. You showed me, by your example, what a good person (and professional should be). Also, I will like to extend my sincere gratitude to Mr. Arnold Deane and Mrs. Venus Gibson for your generosity and goodwill that supported me during the difficult times this study was done. I am grateful to all of those with whom I have had the pleasure to work with during this study.