1. INTRODUCTION

In Mexico, as in other upper-middle-income countries, there has been an alarming rise in mental disorders. Depression, anxiety, and suicide are particularly severe psychiatric conditions affecting young Mexicans, with the prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) in adolescents reaching 16.2%.1

Given the severe and long-lasting impact of psychiatric symptoms on young people, preventive interventions should focus on fostering resilience by helping them develop coping resources and by creating a more supportive psychosocial environment.2

Preventive strategies require early recognition of symptoms, reliable diagnoses by trained professionals, timely initiation of treatment, and adequate access to mental health services. However, significant barriers and inequalities in access to care persist, particularly for rural, low-income, and indigenous groups. In the Americas, it has been estimated that the average treatment gap for severe mental disorders in children and adolescents exceeds 50%.

Regarding indigenous populations, one-third in the United States and 80% in Latin America had not received treatment.3 In Mexico, only 3% of the 544 existing outpatient medical units serve pediatric populations, and there are only 0.20 child psychiatrists per 1000 children.

In this context, remote care has proven effective in improving access to mental health services4,5 effectively provides pharmacological and psychological counseling to primary care physicians in rural or isolated communities.6

The strategy to implement a Remote Primary Healthcare and Psychiatry Model (PHC/PSY) follows an implementation science framework as a guide. This approach outlines specific stages and activities to increase the likelihood of success. The National Implementation Research Network7 proposes four functional stages: (1) exploration; (2) installation; (3) initial implementation; and (4) full implementation over a period of 2 to 4 years. A key component of implementing specialized mental health and psychiatry care is the Primary Healthcare (PHC) personnel and their dimensional characteristics, including the type of care model, the functioning of healthcare centers, healthcare staff characteristics, patient profiles, and the management model.8

Studying PHC personnel characteristics is crucial for health service planning, especially in mental health, where human resources are insufficient and unevenly distributed. This disparity is reflected in the concentration of professionals in urban psychiatric hospitals, while rural and indigenous areas face extremely limited access to mental health care.9 Considering the previous premise, the hypothesis that guided the research is that primary healthcare personnel have limited access to the necessary training and education to identify, treat, and refer mental health cases. This lack of professional preparation, coupled with structural barriers such as limited access to psychiatric medications and a shortage of specialists, reduces the likelihood that individuals will receive adequate and timely treatment in rural and indigenous communities. Thus, this study aims to explore the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of PHC personnel regarding mental health care, specifically for depressive disorders, as well as their perception of professional needs to adopt a new care model, such as the remote PHC/PSY model, and the perceived barriers related to this proposed care model.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Design

This study employed an exploratory, mixed-methods research approach with both quantitative and qualitative components, using a cross-sectional design. The research aimed to explore the knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the care of depressive disorders in rural and indigenous communities. The cross-sectional design captured a representative snapshot of the situation at a specific point in time.

2.2. Setting

The study was conducted in Ciudad Fernández municipality, located in the state of San Luis Potosí, Mexico. San Luis Potosí is one of the Mexican states with the largest number of indigenous language speakers. The total population of San Luis Potosí is 2,822,255, of which more than 17% are between the ages of 15 and 24, representing over 480,000 young people10 Ciudad Fernández is one of 58 municipalities in the state, and along with the Rioverde municipality, it forms the Zona Media, the second-largest metropolitan area in the state after the capital. The 97 communities of Ciudad Fernández lack specialized public health services for mental disorders. The Zona Media has only one psychiatrist, who is based in the only General Hospital for the entire population without social security, serving approximately 146,049 inhabitants.10

The municipality is divided into four geographic sectors, with the rural and indigenous communities located in the most remote areas, such as the communities of 20 de Noviembre and Ojo de Agua de Solano, which have 1,498 and 1,291 inhabitants, respectively. Other communities, like those in the Plan de Arriba sector, are situated in the Sierra Madre Oriental mountain range.

2.3. Participants

The study included 29 out of 30 healthcare personnel from local health facilities, all of whom were part of the Primary Healthcare (PHC) system. These professionals, from various health disciplines, were non-randomly selected to represent the primary health centers in Ciudad Fernández, San Luis Potosí. The inclusion criteria spanned across different health professions, ages, and genders.

2.4. Data Collection (Procedure)

Data collection was conducted in two phases. First, a documentary review was performed, which included statistics, databases, and official literature on the availability of resources for treating depressive disorders among adolescents and young people in San Luis Potosí. This phase helped in the development of the questionnaire and interview guide. In the second phase, surveys and semi-structured interviews were conducted with PHC personnel from local health centers. These individuals were invited to participate individually at their workplaces, with three focus groups organized over three sessions. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study.

2.5. Surveys

The surveys were conducted using a validated, self-administered questionnaire—the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) Assessment Questionnaire.11 This questionnaire covered topics related to the care of depressive disorders in young people, including the identification of barriers and facilitators for timely and quality healthcare. The questionnaire was adapted to include more detailed questions aimed at assessing healthcare personnel’s perceptions of mental health services in their community. A three-point Likert scale was employed to categorize responses, with options for “Agree,” “Not Sure,” and “Disagree.” The scale for weighting responses was used exclusively by the researchers to ensure consistency in data analysis.

2.6. Focus Group Interviews

The focus group interviews were guided by a questionnaire designed to thematically explore mental health care processes for youth accessing PHC services. The questions addressed priorities in depression care, manifestations of depressive symptoms, treatments, and professional needs for delivering effective care.

2.7. Data Analysis

For the quantitative analysis, the statistical software SPSS V.29 for Windows was used. Non-parametric descriptive statistics (NPAR TEST) were applied, including single-sample tests such as Chi-square and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests, depending on the variable type, comparing all KAP questionnaire variables by gender. In addition, we used the Mann-Whitney U test (and the equivalent, the Wilcoxon rank sum test/Wilcoxon 2-sample t test) to compare the rank distributions of study variables between men and women.

The statistical power of the test was 0.8 (80%), indicating that the likelihood of detecting a true effect was sufficient to consider the associations found as statistically significant.

Regarding the qualitative analysis, after conducting the interviews, the field researcher kept a field diary, documenting the perceptions, knowledge, and opinions of the PHC professionals based on the Interview Guide questions. The interviews were transcribed, replacing informants’ names with codes, and the audio recordings were deleted once the transcripts were saved. The data was then organized for inductive analysis using ATLAS.ti v9.1 software. Free coding was employed, creating codes related to PHC professionals’ perceptions of mental health care.

For this first article, verbatim quotes were not included, as the study focused on identifying patterns and themes within the data rather than analyzing specific words or phrases. The analysis stemmed from the responses and interpretation, with special emphasis on the conceptual theory underlying health services research.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

3.1.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

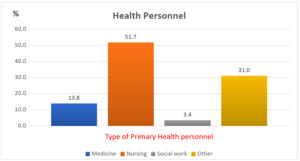

A total of 29 primary healthcare (PHC) professionals participated in the study. Of these, 17% (n = 5) were male, and 83% (n = 24) were female. The average age was 31 years, ranging from 22 to 67 years. Only 7% of participants reported speaking an indigenous language (Pame or Xi’iui). Figure 1 displays the professions of the PHC personnel, with nursing staff being the most prevalent group.

3.1.2. Work Context Characteristics

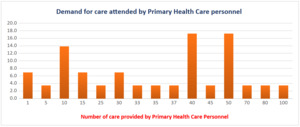

35% of the participants mentioned having one year or less of experience working in PHC, followed by 21% with 2 years of experience, and 10% with 5 years (data not shown). The professionals indicated that the demand for care at the first contact is high, with up to 80–100 consultations per week. See Figure 2.

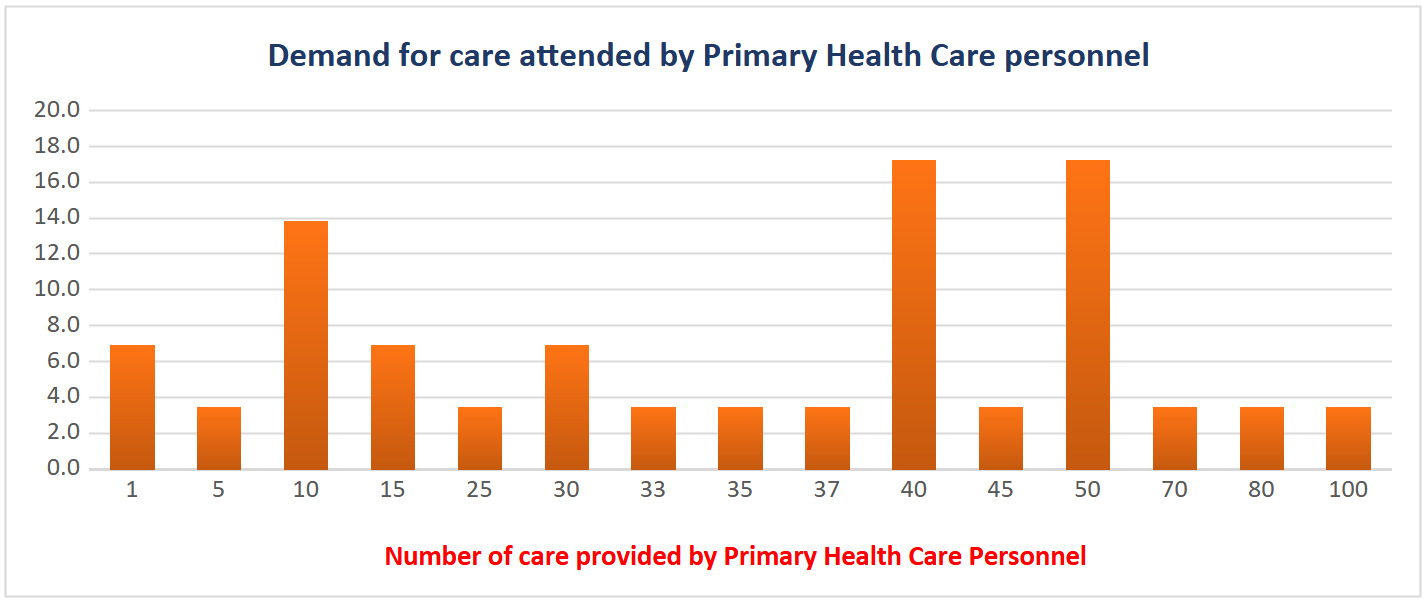

The participants reported variability in the number of young people they attend to, with the majority (24%) reporting an average of 10 consultations. Among the young people served, 38% were identified as speakers of an indigenous language, but only 7% of healthcare professionals could communicate in an indigenous language (see Figure 3).

Although 45% of the healthcare professionals reported that their centers provide care for depressive disorders, only 34% recorded depression as a reason for consultation. Regarding their knowledge of policies, plans, and programs for mental health care, 62% of PHC professionals believed their knowledge was insufficient (see Figure 4). Additionally, 93% expressed a need for more training, 86% indicated an increase in mental health cases in the community, and 38% found treating these cases challenging.

More than half of the PHC personnel reported having received at least one training or refresher course on prevalent mental health problems. However, 93% expressed a need for further mental health training (data no show).

The main perceived barriers to implementation included limited availability of psychiatric medications (66%), a shortage of mental health professionals (62%), and other resource limitations, such as social security and treatment costs (80%).

3.1.3. Gender-Based Comparative Analysis

A gender-based comparison of all variables from the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) questionnaire identified statistically significant differences in the following categories (see Tables 1 and 2).

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

The main themes explored in the three focus group interviews, with 10-15 participants each, are summarized below:

3.2.1. Prevalence of Depression in the Community

Participants discussed the most common manifestations of depression in both indigenous and non-indigenous communities. They highlighted the increase in suicide cases, particularly among adolescents and youth, often linked to family issues, bullying, and social pressures.

3.2.2. Influence of Social Media and Substance Use

The group addressed how the widespread use of social media and the increase in substance use have contributed to the rise in mental health problems, particularly depression and suicide risk.

3.2.3. Care Demands and Reasons for Consultation

Main Demands: PHC professionals in both indigenous and non-indigenous communities identified common mental health-related demands, such as isolation, rebellion, and difficulties with problem-solving and learning among adolescents.

Reasons for Consultation: Parents were often the primary motivators for seeking care, concerned about their children’s isolation, behavior, and sexual health. However, mental health issues, particularly related to emotions and behavior, emerged during consultations.

3.2.4. Contributing Factors and the Impact of Family Environment

Risk Factors: Discussions revealed that parental separation and strict parenting practices often led to anxiety in adolescents, exacerbating pre-existing suicidal ideation. The pandemic was also cited as a factor that increased social anxiety during the educational transition.

3.2.5. Care and Detection of Depressive Disorders in Health Centers

Clinical Pathway: The clinical pathway was described, from somatometry to medical consultations, with referrals to psychology or the municipal DIF in cases of depressive symptoms.

Challenges in Early Detection: The lack of uniform strategies for early detection of depressive symptoms in young people was emphasized, with detection largely depending on the knowledge and willingness of the professional on duty.

3.2.6. Barriers and Needs in Care

Access Barriers: Obstacles to receiving mental health and psychiatric care included parental resistance and treatment costs. The lack of adequate patient follow-up was also identified as a significant barrier.

Identified Needs: Continuous training for professionals was a common need, as participants highlighted the lack of specialized personnel and specific care programs. They also noted positive changes over time, recalling a successful psychiatric care program that provided free medications six years ago. Although there has been more interest from some authorities, participants stressed the need for a comprehensive strategy and widespread training to provide humane and quality care.

4. DISCUSSION

The analysis of this study revealed that primary healthcare personnel have limited knowledge about depressive disorders in youth and face significant barriers to providing adequate care, such as a lack of training and resources. The results also suggest that the implementation of a primary healthcare and psychiatric model (PHC/PSY) could improve access to and the quality of care in these rural and indigenous communities, although additional measures for training and structural support are needed. These relevant findings are discussed below.

The sample, composed mostly of female professionals, reveals “the feminization” of the workforce in the health sector, a global phenomenon recognized as significant in health care delivery.12 The unequal gender distribution in this PHC context could influence care dynamics, as reported in another study.13 However, in this exploration, we report an equal commitment and sensitivity towards mental health care among genders. In fact, a recent study showed that females had a greater perception in identifying mental symptoms in children and adolescents, which would strengthen their involvement in prevention strategies for depressive disorders.14

The analysis of the work context reveals the considerable workload faced by PHC professionals, with up to 100 consultations weekly. This high demand could affect the quality of care in PHC, as noted in a systematic review study.15 It also underscores the need for support and stress management strategies for health personnel. One approach is to provide training and skill development aimed at improving care processes, as proposed in the MAP/PSI.

The professionals’ perceptions regarding the management of depressive disorders reflect a discrepancy between the service offerings and actual demand. Although 45% stated that their workplaces provide care for these disorders, only 34% reported having provided care to young people with depression. This gap suggests possible barriers in detection or a lack of proper follow-up for patients. As reported in another study, there is no standard for detecting psychological symptoms.16 Although the reported studies focus on populations with other chronic health conditions, not mental disorders.17,18

On the other hand, the findings from the qualitative component add depth to these results by exploring the complexities of mental health care in community contexts. Professionals highlighted the increase in suicide cases, attributed to factors such as family problems, bullying, and social pressures, findings similar to those reported in the literature.19 The negative influence of social networks and the rise in the consumption of psychotropic substances emerged as additional concerns, emphasizing the need for comprehensive preventive strategies.

The care demands identified in the interviews, such as isolation and rebellion in adolescents, underscore the importance of early and proactive care. However, challenges in early detection highlight the lack of uniform strategies in health centers, emphasizing the need for standardized protocols to improve the identification and management of depressive disorders in youth.

The perceived barriers to implementing the Primary Care and Remote Psychiatry Model (MAP/PSI) are consistent with the scientific literature.20 The limited availability of psychiatric medications, the shortage of mental health professionals, and restrictions in economic and social resources are challenges identified by the professionals. These results support the importance of addressing not only the training of health personnel but also the infrastructure and resources needed to implement effective interventions.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The conclusions suggest the need for a comprehensive strategy that addresses the multiple dimensions of mental health in young people in community settings. Ongoing training for health professionals, the implementation of standardized protocols, and strengthening infrastructure are essential for improving care. Additionally, the widespread acceptance of the remote care model indicates an opportunity to leverage telemedicine and overcome geographical barriers. This opportunity scenario can be enhanced if public policy decision-makers take into account the community’s perception of feasible strategies.

Ethical aspects

To comply with ethical aspects of research involving human beings, the study protocol was submitted and approved by the Ethics Committee in Research of the National Institute of Psychiatry Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. Registration CEI/C/034/2022.

Declaration of interests

Article elaborated as part of the Research Project: Implementation of a remote Primary Health Care and Psychiatry Model (PHC/PSY), focused on early diagnosis and timely treatment of depressive disorders in young people aged 15 to 25 in rural and indigenous communities of San Luis Potosí, Mexico. Financed by Fundación Gonzalo Río Arronte I.A.P., Project S.736; and the National Institute of Psychiatry Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz, Project EP22174.

Conflict of interest

None declared by the principal author.