1. Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a pathological response to traumatic events, characterized by intrusive memories, avoidance behaviors, hyperarousal, and cognitive distortion.1 Alexithymia, a construct defined as difficulty identifying and describing emotions, has been linked to poorer therapeutic outcomes and chronic PTSD symptomatology.2 While prior studies highlight the prevalence of alexithymia in trauma-exposed populations, data from Latin America remain scarce.

Globally, PTSD affects approximately 3.9% of the population, with higher rates reported in high-income countries (5%) compared to low- and middle-income nations (2.1–2.3%).3 In Mexico, the estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD is 1.5% and women are the most affected.4 Alexithymia’s role in PTSD pathophysiology remains underexplored. Longitudinal studies suggest that deficits in emotional processing may exacerbate PTSD symptoms by impairing adaptive coping mechanisms.5 Furthermore, trauma exposition duration may interact with alexithymia to influence symptom trajectories. While prior research has established a link between alexithymia PTSD, most studies focus on high-income countries or specific populations (e.g., war veterans, Holocaust survivors). Data in populations exposed to other stressors such as sexual or physical abuse are scarce. This study aimed to provide information on the prevalence of alexithymia in Mexican patients with PTSD and to analyze trauma duration as a potential predictor of alexithymia severity. We hypothesized that the frequency of alexithymia exceeds 50% in outpatients with PTSD.

2. Methods

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted between March and May 2023 at the outpatient clinic of Hospital Psiquiátrico Fray Bernardino Álvarez in México.

2.1. Selection criteria

Participants included Spanish-speaking adults (≥18 years) diagnosed with PTSD. Exclusion criteria comprised comorbid psychiatric conditions associated with alexithymia (e.g., depressive disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders). PTSD diagnosis was confirmed using the Spanish-validated CAPS-5.6

2.2. Variables

Sociodemographic variables: age, sex and educational attainment, categorized using the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED-2011).

Clinical variables: trauma type (e.g., interpersonal violence, accidents, sexual assault), duration of trauma exposure in years, and TAS-20 total and subscale scores.

2.3. Instrument

Alexithymia was assessed with the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (cutoff ≥61; Spanish version, Cronbach’s α = 0.82).7

2.4. Statistical analysis

Sample size estimation determined a minimum requirement of 81 participants (estimated prevalence of 4.5%, confidence level of 97%, significance (α) of 0.05, and statistical power of 1.0). Frequencies and percentage were described for qualitative variables. Measures of central tendency and dispersion were described for quantitative variables. The distribution of the data was verified with the Kolmorodov-Smirnov test. Non-parametric analyses were applied due to non-normal data distribution: Spearman’s correlation, Mann-Whitney U tests, and binomial logistic regression. Accepted statistical significance was pz0.05. We used EpiInfo™ 7.2.6.0 to statistical analysis software.

3. Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Mexican Official Standard NOM-012-SSA3-2012 and Title II, Chapter 1, Article 17 of the General Health Law, classified as low-risk research. Ethical principles were upheld, including personal data protection, voluntary participation through informed consent detailing study characteristics, and the use of a validated instrument to quantify alexithymia. Confidentiality of participant data was maintained exclusively for research integration purposes. The study was monitored by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Psiquiátrico Fray Bernardino Álvarez, and no financial costs or compensation were provided to participants.

4. Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

The sample comprised 101 patients who met criteria for PTSD (91% female, mean age: 29.5 years). The majority of patients had a Upper Secondary diploma (ISCED 3) (49.5%, n=50), followed by Lower Secondary diploma (ISCED 2) (26.7%, n=27), a Bachelor’s degree (ISCED 6) (17.8%, n=18), and the remainder completed Elementary School (ISCED 1) (5.9%, n=6). Most patients were employed at the time of sampling (56.4%, n=57). The remaining cohort included unemployed individuals (16.8%, n=17), those engaged in domestic duties (14.9%, n=15), and students (11.9%, n=12).

Trauma exposure

The majority of patients experienced sexual abuse (53.5%, n=54), followed by sexual assault (26.7%, n=27), physical abuse (14.9%, n=15), human trafficking or kidnapping (4%, n=4), and one patient (1%) survived war exposure. Patients under 29 years old experienced significantly higher rates of sexual abuse compared to other age groups (χ² = 32.145, p < 0.05). Distribution of trauma types by age group can be seen in Table 1.

The mean duration of trauma exposure was 10.38 months (SD = 8.6), ranging from less than 1 month to 36 months. The 25th percentile corresponds to less than 4 months of exposure, while the 75th percentile exceeded 16.2 months. Notably, 11.2% of patients (n=11) reported exposure durations of less than one month.

Alexithymia screening

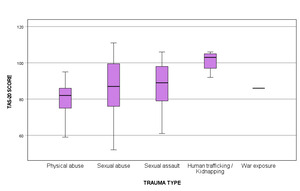

90% of patients (n=91) scored above the TAS-20 threshold for clinical alexithymia (>61 points). Possible alexithymia (scores between 52–60 points) was identified in 6.9% (n=7), and only 3% (n=3) scored ≤51 points, indicating no alexithymia. No statistically significant difference in TAS-20 score classification was observed between sexes, age groups or educational attainment level groups. Patients exposed to human trafficking/kidnapping had higher TAS-20 scores (p= 0.005). Graphic 1

When analyzing domain scores among patients classified with Possible Alexithymia and Alexithymia, the following results were observed: Sensory Discrimination (D1): Mean score of 31.2 points (range: 18–42); Verbal Expression (D2): Mean score of 21.9 points (range: 11–30); Detailed Thoughts (D3): Mean score of 32.1 points (range: 18–46).

When comparing patient groups classified with Possible Alexithymia and Alexithymia based on total Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20 (TAS-20) scores, mean scores across all domains were significantly higher in the Alexithymia group. Table 2.

Correlational analysis

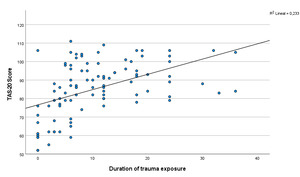

A moderate positive correlation was observed between duration of trauma exposure and total TAS-20 scores (Spearman’s rs = 0.539, p < 0.001), indicating that longer trauma exposure was associated with higher alexithymia severity. Also, duration of trauma exposure showed a positive correlation with TAS-20 subscales total scores (D1: r = 0.524, p < 0.001; D2: r = 0.485, p < 0.001; D3: r = 0.509, p < 0.001).

Upon the risk analysis, it was identified that only a high school education level exhibited a significant association with an increased probability of presenting alexithymia, demonstrating a 160% elevation in risk compared to baseline. This finding contrasts with the remaining sociodemographic and trauma type variables analyzed, none of which showed a significant correlation with alexithymia incidence. Table 3.

A binomial logistic regression analysis was performed using a backward stepwise method, incorporating variables correlated with alexithymia scores in the risk analysis of this study, as well as additional risk factors documented in the literature. The final model revealed that time of exposure to trauma was the sole variable significantly associated with an increased risk of alexithymia (AOR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.24–2.48, p < 0.05). Table 4.

5. Discussion

Regarding the alexithymia score, most PTSD patients (90%) scored above the diagnostic threshold on the Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20, so the hypothesis was accepted. In the general population, alexithymia prevalence ranges between 10%–14%, with higher male scores observed in Germany, Finland, and the U.S.8–10 A 2023 study of Dutch police officers exposed to trauma (n=38; 18 females) versus non-PTSD controls (n=40; 20 females) confirmed elevated alexithymia levels in PTSD patients, independent of trauma exposure, reinforcing its role as a clinical phenotype.11 Similarly, Yehuda’s (1997) analysis of Nazi concentration camp survivors revealed significantly higher TAS-20 scores in PTSD-diagnosed individuals versus non-PTSD counterparts.12 A prospective study of 86 Iraqi refugees (32 with PTSD; 23 males, 9 females) also linked PTSD to higher alexithymia scores, primarily driven by TAS-20 Factor I (difficulty identifying emotions), which correlated with self-reported dysphoria.13

In this study, no sex-based differences in alexithymia were observed, consistent with global reports showing no significant gender disparity in its association with PTSD.11,14 By trauma type, physical abuse survivors had the lowest mean TAS-20 scores, followed by sexual violence victims. Participants exposed to human trafficking/kidnapping scored highest. However, these results lack generalizability due to unmeasured individual vulnerability/resilience factors. Furthermore, no patients in this subgroup lacked alexithymia, precluding calculation of crude/adjusted risk ratios.

Concerning trauma duration, participants averaged over 10 months of exposure. However, prior studies have not systematically evaluated this variable, precluding definitive conclusions about its role in symptom development. This gap may reflect heterogeneity in trauma conceptualization, as stressor magnitude, resilience, and post-traumatic growth are influenced by biological, environmental, and contextual determinants.15 Human behavior constitutes a dynamic, adaptive system wherein individuals oscillate between functional and dysfunctional responses. Understanding post-traumatic outcomes requires analyzing risk factors, protective mediators, and individualized coping mechanisms.16 Beyond trauma type, dimensions such as event intensity, negative valence, external/uncontrollable stimulus source, and unpredictability significantly influence PTSD severity.17–19

Among collected variables, only trauma duration exhibited a moderate positive correlation with alexithymia (TAS-20) and emerged as a significant risk factor. Trauma exposure duration increased the probability of post-traumatic alexithymia by 75% compared to age, primary/bachelor’s education, or trauma type (sexual violence/trafficking).

The findings of this study align with and extend emerging evidence on the complex interplay between alexithymia, psychological distress, and PTSD. Consistent, with research by Putica et al, which identified psychological distress as a partial mediator between alexithymia and PTSD hyperarousal symptoms across multiple time points.5 Our results underscore the enduring role of distress in amplifying PTSD severity, notably, same author also reported that psychological distress fully mediated re-experiencing and avoidance symptoms, a finding paralleled in our results, suggesting that alexithymia’s influence on these clusters is contingent on concurrent distress levels.

Furthermore, our results resonate with Ennis et al., who demonstrated that alexithymia moderates the relationship between specific behavioral coping responses (e.g., immobilized reactions during sexual assault) and PTSD severity. While our study did not explicitly assess trauma-type-specific responses, the observed interaction between trauma duration and alexithymia echoes their conclusion that individuals with limited emotional awareness are disproportionately vulnerable to PTSD when exposed to prolonged or immobilizing stressors.20 Further highlighted that diplomatic coping strategies (e.g., indirect resistance) were associated with PTSD only in high-alexithymia individuals, implying that emotion-processing deficits may distort posttraumatic appraisals of such responses. This aligns with our finding that trauma duration—a proxy for chronic stress exposure—correlated positively with alexithymia, suggesting that prolonged trauma may entrench maladaptive coping mechanisms in those with preexisting emotion-regulation deficits.

However, contrasts exist between populations. Ennis et al., focused on sexual assault survivors, where immobilized responses and alexithymia synergistically increased PTSD risk, whereas a military sample exhibited no gender-specific effects.20 This discrepancy may reflect differences in trauma typology (interpersonal vs. combat-related) or cultural factors influencing help-seeking behaviors. Nevertheless, both studies converge on alexithymia’s role as a transdiagnostic risk amplifier, particularly in contexts where emotional processing is critical to recovery.

Limitations of the study: Sample included predominantly female participants in a single outpatient scenario, which limits the generalizability of the findings to male and culturally diverse population. A cross-sectional study precludes causal inferences between trauma exposure duration, PTSD, and alexithymia. PTSD severity was not assessed which could confound the relationship between trauma duration and alexithymia. Individual resilience, pre-trauma psychological functioning, and social support were not evaluated, though these factors may mediate or moderate the observed associations. Reliance on retrospective self-reports of trauma duration may introduce recall bias, particularly in participants with dissociative symptoms or cognitive distortions from PTSD.

Conclusion

Alexithymia, identified via screening with TAS-20, was prevalent across all age groups in the sample. Notably, human trafficking and kidnapping were associated with the highest TAS-20 scores. Furthermore, trauma exposure duration demonstrated a significant positive correlation with total TAS-20 scores, a pattern consistently observed across all three TAS-20 subscales. Trauma exposure time is an underreported variable in PTSD and alexithymia research. This measure may function as either a risk factor or a confounding variable mediating the association between alexithymia scores and PTSD severity. The lack of standardized measurement and reporting of trauma duration in existing literature underscores the need for rigorous methodological frameworks to clarify its role in trauma-related psychopathology.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in Mexico to identify trauma duration as a critical predictor of alexithymia in PTSD. These findings highlight the clinical relevance of quantifying trauma exposure duration and its potential bidirectional relationship with alexithymia. Further studies are warranted to disentangle its mechanistic contributions.

Funding

Self-funded; no conflicts of interest declared.

Conflict of interest

We declare no conflict of interest.